New technology means new opportunities — and anxiety for today’s workers

In the history of the United States, there has been an unshakable bond between the idea of hard work and prosperity, a relationship author James Truslow Adams eloquently described as “the American Dream,” a term he coined.

In the history of the United States, there has been an unshakable bond between the idea of hard work and prosperity, a relationship author James Truslow Adams eloquently described as “the American Dream,” a term he coined.

The American dream is “that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement,” Adams wrote in 1931.

However, to many people, the rapid pace of technological change appears to be eroding that linkage. Working hard is fine — as long as you have work. Emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and automation seem more likely to replace us than help us.

Indeed, global consulting firm McKinsey & Co. estimates that in 60 percent of all occupations, at least 30 percent of job activities can be automated.

The truth is that the American dream and technological advancement have always gone hand in hand. The original European colonists who migrated to America in the 17th century looking for gold eventually found ways to grow tobacco and cotton instead. The agrarian life they established gave way in the 19th and 20th centuries to factory workers who migrated to big cities to pump out clothes, cars and appliances. Today, people flock to the United States, especially Silicon Valley, to write software code for smartphones and self-driving cars.

In other words, as technologies change, so does the economy, often for the better. Technologies no doubt destroy industries and jobs but also create new opportunities and markets, frequently in the most unexpected ways.

“It all depends on consumer demand,” said James Bessen, an economist who serves as executive director of the technology and policy research initiative at Boston University School of Law. “And it’s really hard to anticipate all of the things that consumers will want to buy or do.

“People assume that automation means a decline in jobs, but that’s simply not true,” said Bessen, author of “Learning by Doing: The Real Connection Between Innovation, Wages, and Wealth.” “Automation means things move faster, but speed doesn’t necessarily mean jobs will suffer. Speed can mean new jobs are being created faster.”

The real question is how technology boosts productivity, or how the economy produces goods and services in the most efficient way possible. Capital and labor are finite resources, so doing more with less means lower prices for those goods and services. And as more and more people can afford things, the market grows to a point where companies need to hire workers to meet demand.

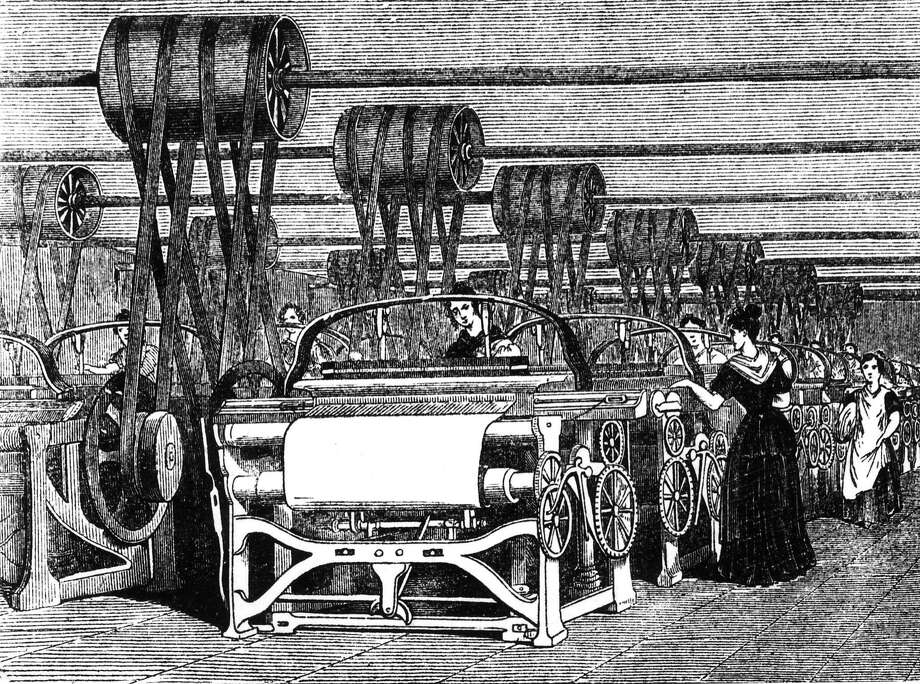

According to Bessen’s research, weavers on power looms at first could produce 2.5 times as much coarse cloth per hour as a weaver on a hand loom. Over the ensuing decades, advances in power loom technology generated another 20-fold increase in output per hour.

You might assume that power looms wiped out jobs for weavers. Yet from 1830 to 1900, the number of weavers in the United States quadrupled.

Why?

“Because automation also increased demand,” Bessen wrote in his book. “With progressively lower costs, prices fell, consumers demanded more cotton cloth per capita, and there was more demand for weavers.”

The automobile is a good example of technology destroying one industry but creating a new, much larger market.

Famed industrialist Henry Ford’s innovations in assembly line production made cars affordable to the masses. Demand for Model T’s soared, which meant Ford needed to hire lots of workers to make them. His methods allowed automakers to eventually manufacture heavier vehicles like trucks more cheaply, giving birth to the transportation and logistics industries.

People thought ATMs would replace bank tellers. But banks continue to build branches because when it comes to money, consumers still want to interact with humans.

The emergence of the Internet in the late 1990s no doubt hurt older industries like department stores and newspapers. Since consumers can more efficiently buy goods or read news stories over the Internet, companies have closed stores and shrunk paper publications. But the Internet created huge demand for software engineers.

For another modern example, look at the boom in television that has accompanied the rise of Netflix. If this is disruption, flush Hollywood studios are saying, give us more. And actors aren’t the only ones to benefit: The industry is set to create tens of thousands of well-paying jobs for camera operators, video editors and more, according to a Bureau of Labor Statistics forecast.

On the flip side, the Internet also means innovation can be quickly duplicated. New advances in one company’s smartphone will soon be found in competing devices around the world.

Perhaps that’s one big reason why wages have stagnated in recent years. New products have failed to stimulate consumer demand because there are too many similar things already present or soon to appear on the market. Without consumer demand, companies have little reason to hire people or pay them more.

John Williams, president of the Federal Reserve Bank in San Francisco, said only truly breakthrough technologies, like artificial intelligence, can really boost the economy over the long term in a sustainable way.

Some experts predict that self-driving cars, powered by artificial intelligence, will transform the physical makeup of the city. There will be less need for large parking lots and garages because autonomous vehicles don’t need to stop for long periods of time. That frees up people to redevelop real estate for housing, low-cost commercial buildings, or even public spaces.

“You can get all of that land back,” Gorenberg the venture capitalist said. “There will be a huge number of opportunities in construction to create smaller, more compact buildings in these spaces and allow people to be closer to the jobs.”

Another promising, underestimated technology is 3-D printing.

Right now, 3-D printers can produce relatively simple things like coasters, whistles and page holders.

“With 3-D printing, you can make interesting, fun little structures that sit on your table,” said Shane Wall, chief technology officer for HP Inc. in Palo Alto and director of the famed HP Labs. “It’s nice, but you’re going to have to do a lot more than that.”

Wall envisions a time when large factories equipped with enormous 3-D printers can produce anything — even cars and electronics — at a fraction of today’s costs. That may hurt employment in big, conventional factories overseas, but it might also eliminate the need for companies to send manufacturing jobs to those lower-wage countries in the first place.

Companies can set up digital-manufacturing facilities closer to where customers actually live, further reducing costs for things like transportation and warehousing, Wall said.

“It will radically change where we do manufacturing,” he said. “The way technology is going, manufacturing will come back to the United States. And it’s gonna come back in a way you never thought about.”

That’s probably little comfort to workers today, who fear the Internet-driven economy is leaving them behind.

Normally, technological changes require decades to really take effect. The Internet, however, has transformed the economy at unprecedented speed. The prospect of self-thinking computers will only turbocharge that change.

In decades past, we believed that once we achieved fulfillment and success, our work was done. But the economic and sociological disruption wrought from technological advancement requires us to remain vigilant, to not take anything for granted.

For it’s not enough to merely obtain the American dream. We must now work harder than ever to hold onto it.

Source:-sfchronicle