Yale Researchers Find the Part of the Brain That Determines How Well You Handle Stress

Humans are amazingly resilient in crises, but some cope with life’s stresses better than others.

Humans are amazingly resilient in crises, but some cope with life’s stresses better than others.

On any given day people face any number of minor annoyances such as being stuck in traffic or spilling coffee on their shirts or forgetting their keys. Then there’s the persistent stressors that come from work, relationships and finances. And there’s the uncontrollable anxieties of global terrorism, mass shootings and Zika-carrying mosquitoes.

But why are some people able to deal with it all so calmly, while others freak out?

A team of researchers at Yale University may have found the answer in the brain.

The scientists studied the brains of 30 adult volunteers with no history of mental or physical health issues as they watched a slideshow of gruesome and terrifying images for six minutes. To compare brain activity, they then showed the participants benign images that would evoke little emotion, such as a photo of a chair.

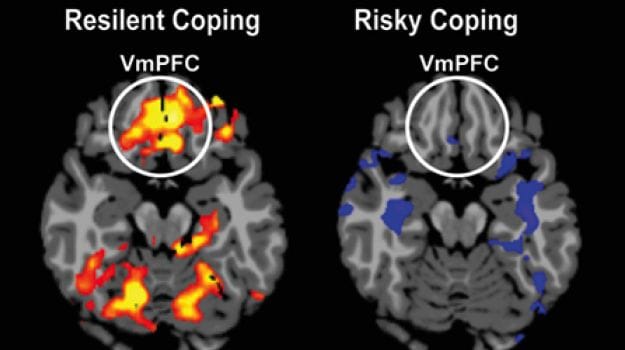

They located three areas of the brain that responded to the stress of seeing photos of people mutilated or at gunpoint or in other harrowing scenarios. But what the researchers found most interesting was how the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), which processes risk and emotional response, adapted while viewing the photos.

In everyone, activity in that region decreased initially in response to the images, as though their guard was down, but then in some people, it became hyperactive, as if working overtime to control the emotional response, or in other words, to cope.

“We have not had a way of breaking that apart to see what the brain is doing,” said Rajita Sinha, director of the Yale Stress Center and lead author of the study. “How do we cope in the moment? Here, we said, in the moment under acute threat how does the brain cope and regain control?”

Moreover, Sinha found through subsequent interviews with the study participants that those whose vmPFC did not bounce back quickly under stress were also susceptible to binge drinking, emotional eating and fighting. These maladaptive behaviors may be because their brains do not cope well in stressful situations and then lead to self-destructive actions, Sinha said.

This evidence shows that people’s response to stress may be physiological, and Sinha said the discovery could lead to developing treatments to improve coping skills. It could be used to identify people who might have a harder time recovering emotionally after a traumatic event or to help people with chronic stress conditions.

Treatments could include behavioral techniques like practicing mindfulness that have proven to be successful in rewiring the brain, she said.

“Some people are stuck with the life they have, the chronic stresses they have. Perhaps by building in certain strategies, you can beef up this part of the brain,” Sinha said. “It’s very hopeful because it brings the physiology to the forefront.